- Authors: Chris West, Gabriela Rabeschini, Chandrakant Singh, Thomas Kastner, Mairon Bastos Lima, Ahmad Dermawan, Simon Croft & U. Martin Persson

- Date: April 2025

- Link to the article

Unpacking global deforestation footprint: How agriculture, trade, and consumption shape forest loss?

Global forest loss is a critical concern, deeply entwined with climate change, biodiversity loss, and sustainable development. Our new review published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment unpacks how agriculture and forestry drive deforestation and how global consumption patterns are inextricably linked to this environmental crisis through what is called the deforestation footprint.

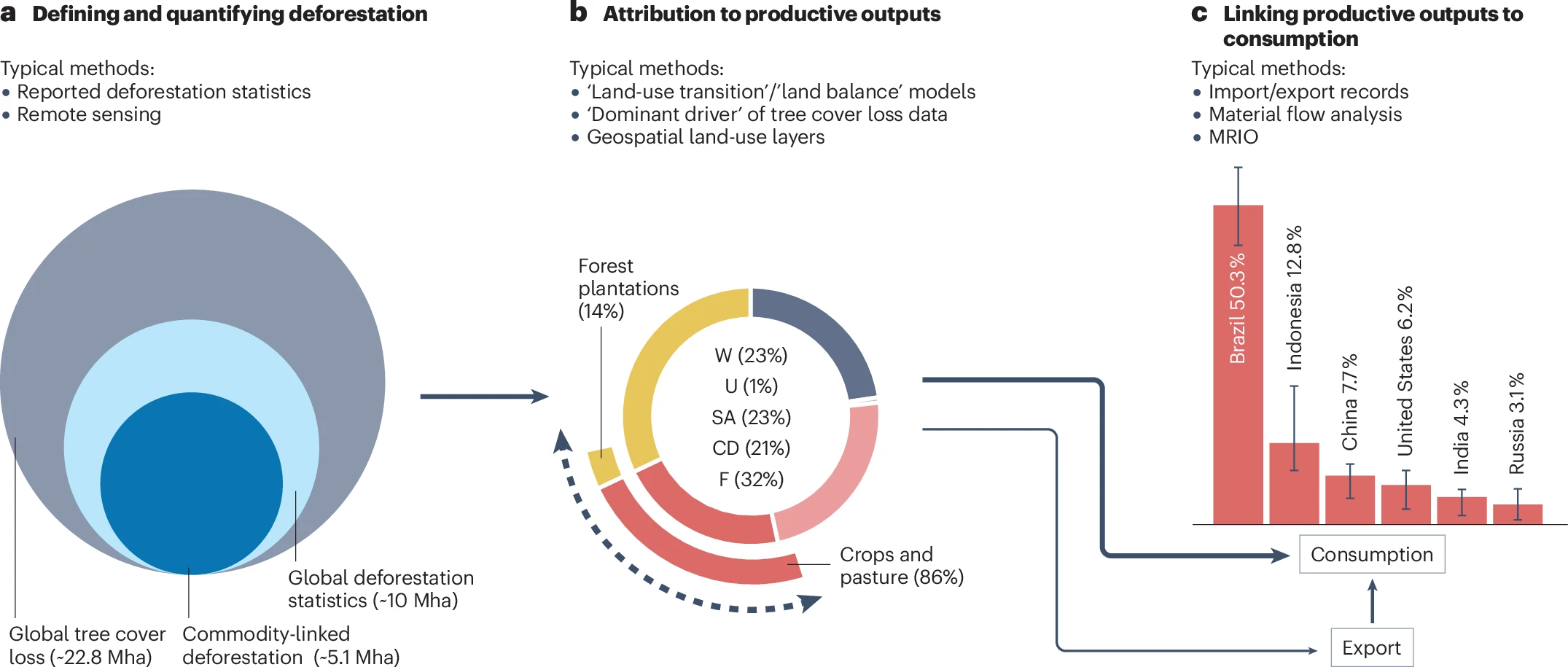

Deforestation footprinting is a method used to trace deforestation embodied in the production and consumption of specific commodities. This powerful tool reveals not only where trees are cut down, but why — and for whom. Between 2001 and 2022, a staggering 86% of global deforestation was attributed to crop and cattle production. Agriculture, particularly in tropical regions like Brazil and Indonesia, stands out as the dominant driver. For instance, over 12.8 million hectares of forest were lost in Brazil between 2005 and 2015 due to agriculture alone.

The review highlights a suite of methods used to estimate deforestation footprints. These range from early regression models to advanced satellite remote sensing, and include approaches like the land balance model, dominant driver analysis, and the DeDuCE model.

Each method varies in how it defines deforestation, attributes causes, and links these to consumption — creating differences in the estimates produced.

For example, the land balance approach uses FAO data and remote-sensing to attribute forest loss to crop or pasture expansion. The dominant driver approach relies on geospatial datasets to classify forest loss by cause, such as agriculture or forestry.

Meanwhile, DeDuCE blends these approaches and includes quality scoring to reflect data uncertainty. Importantly, these methodologies have consistently identified beef, oil palm, and soy as leading drivers of deforestation.

Footprinting also reveals which countries are responsible. Brazil, Indonesia, China, the United States, and Europe are among the top contributors to global deforestation footprints. Notably, a significant portion of this footprint is linked to consumption in countries far from the site of deforestation. For example, a large share of deforestation in South America and Southeast Asia is driven by demand in Europe and China, either through direct commodity imports or re-exported products.

Beyond agriculture, the review draws attention to the underrecognized roles of aquaculture, mining, and infrastructure in forest loss. Mangrove deforestation for aquaculture and forest clearance for small-scale mining are examples where footprinting is limited by data availability.

These gaps highlight the need for better datasets and integration of non-agricultural drivers in footprint models.

Despite its limitations, deforestation footprinting is proving crucial for governance. It informs regulatory initiatives like the EU Deforestation-Free Products Regulation and the UK's due diligence laws, which aim to hold supply chains accountable. With continued advancements in data and methods, footprinting can guide stronger, more equitable land-use governance — identifying not just where trees fall, but who bears responsibility and how policy can respond.